Introduction | Childcare in Disasters | Broadband in Education | Mental Health and Well-Being | Emergency Shelters and Housing Security | Food Security and Poverty | Summary

Childcare in Disasters: Executive Summary

Childcare is a critical service provided for working families, but the provision of childcare currently requires an array of ad hoc waivers in emergency legislation in order to safely continue service provisions when disasters occur. While safety is necessary, the varying requirements and processes for re-opening can lead to delays and additional burdens on childcare providers. Without adequate support for maintaining or reopening childcare programs during or after emergencies, working families struggle to return to work and normalcy. The economy cannot effectively return to normal if parents are unable to return to work. Decision-makers can ameliorate these challenges by supporting policies that elevate childcare services as essential businesses, similar to the essentiality of food services or utilities.

What Are Communities Saying?

Scroll to the left or right to see what communities across America are saying about childcare and disasters in their area.

Spotlight on: New Hanover County, North Carolina

Childcare centers in New Hanover County and other communities have faced the pressure of reopening while meeting stringent new COVID-19 safety requirements despite losing a significant amount of revenue during the first wave of the pandemic. On March 30, 2020, the state forced the closure of all non-essential businesses, causing significant revenue loss. Childcare centers remained open in an extremely limited capacity, exclusively accepting the children of essential workers – this forced the closure of many centers whose clientele do not include essential workers. On May 8th, many non-essential workers returned to their jobs, but childcare facilities remained closed to all but essential workers for an additional two weeks. The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) requirements for reopening were conditional upon completing an application detailing health and safety guidelines to combat future outbreaks of the virus.[i] These requirements compounded existing hardships, considering adjustments made to limit staff schedules in response to budget cuts. In many cases, childcare workers in New Hanover County could not survive on a limited salary and would lose critical unemployment benefits by choosing to return to work. By late May 2020, centers were facing funding and staffing shortages, even as the state mandated reopening of services to all households with caregivers returning to work.[ii]

An additional stressor in this sector is the possibility of positive COVID-19 cases at childcare centers. Centers must incur costs of maintaining safe environments to minimize transmission among staff and children, but the childcare industry workers are not protected as “workers at increased risk” in legislation (including H.R.6559 COVID-19 Every Worker Protection Act of 2020). Childcare centers cannot ensure all participating families are taking appropriate precautions to reduce the risk of contracting the coronavirus at home. These uncertainties and the insufficient support to centers have led to many caregivers choosing to abstain from the service altogether. In addition, private businesses and the public sector have failed to establish widespread paid leave for all parents and caregivers who are not willing or able to put their children into childcare centers during the pandemic, forcing many families to choose between childcare or paid work.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, government subsidies were given to certain types of New Hanover’s childcare facilities on a weekly basis. However, at the onset of the pandemic, this interval was stretched to every 45 days. The increased financial stress placed on the childcare sector created impossible conditions for centers to adapt to necessary changes in operation. Furthermore, childcare facilities struggled to rapidly rewrite budgets during times of great uncertainty and to offset costs of resources, such as broadband, because they are highly dependent on their funders for approval of critical budget adjustments. Some childcare centers in New Hanover County were not authorized to use funds flexibly in response to the immediate crisis, as they were beholden to funding restrictions from specific sources.

Non-local funders continue to make critical decisions for the county’s institutions, including requirements regarding funding for certain organizations or programs, which do not meet the needs of New Hanover County’s childcare centers. These critical decisions, which impact the state-wide health of child-serving institutions, are being made without the vital community input necessary for making effective policies at the local level.

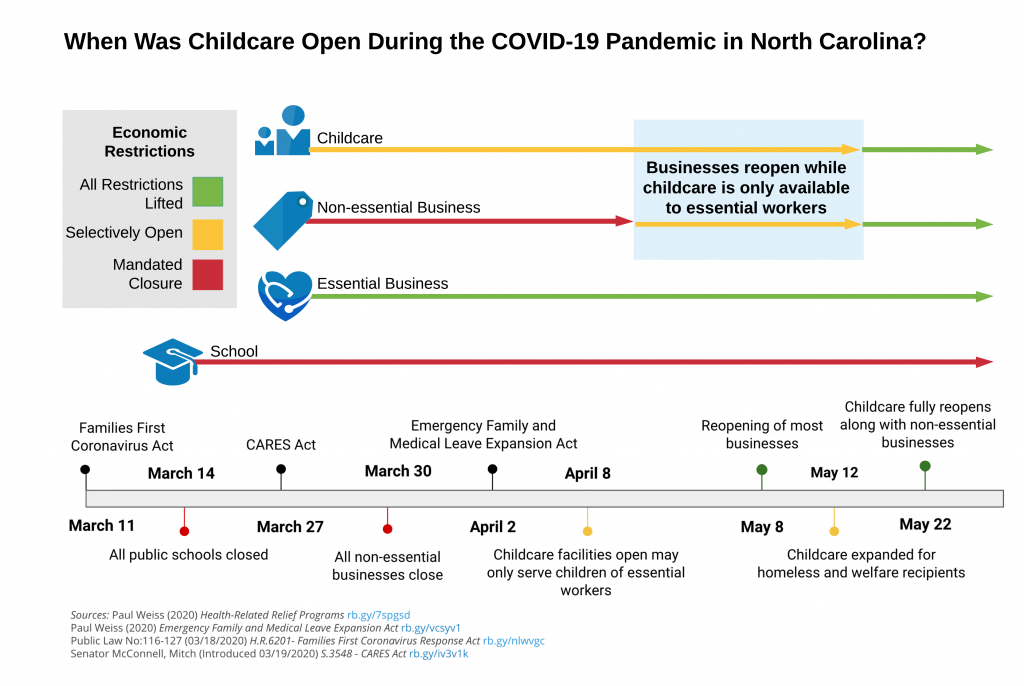

COVID-19 Closures and Childcare in North Carolina

This timeline shows that in North Carolina there was a two-week gap when many adults had to return to work but did not have access to childcare services because they hadn’t yet reopened. At the same time, separate provisions needed to be made for school-age children as schools remained closed. Gaps such as this one create financial hardships and stress for households across America but could be mitigated if childcare services had support to reopen along with essential businesses.

Meeting the Needs of America’s Children

Current government policies in the legislative and executive branches are inconsistent in supporting the needs of the childcare sector. FEMA highlights daycare as a “critical facility” – but only in terms of infrastructure, excluding services.[iii] In the most recent update to the National Response Framework for disasters, Emergency Support Function #6 – Mass Care classes childcare as “essential community relief” but all 6 instances of childcare services lie within the purview of participatory NGOs, meaning they are not governmentally supported or mandated other than through memoranda of understanding.[iv] The “Childcare is Essential Act” (S.3874 and H.R.7027) is a Congressional proposal to elevate this industry and protect its essentiality, which has bipartisan support, passing the House in July 2020 after being introduced to the Senate in June.

As a result of current national and state-level legislation related to childcare, access to childcare services is unequally distributed between races and socio-economic levels. Black and Hispanic working adults with a subsistence-level income experience outsized difficulty adapting to the restricted economy due to loss of childcare which exacerbates the scarcity of this essential service in known “childcare deserts”. [v] This issue not only impacts how quickly and effectively the country can reopen and recover economically in the aftermath of the pandemic, but also amplifies inequalities in income and education, as well as moving the country further from racial and geographic equity while most likely causing a mass decline in the number of women in the workforce.[vi]

Effective national and state-level childcare policies could mitigate hardship for many families across the country but are currently falling short of aiding working families. The typical working family with a small child spent at least $12,000 on childcare in 2015, while federal and state-level childcare subsidies only aid one in every six children in need of support. [vii] [viii] Similarly, the $99 billion childcare industry continues to flounder during COVID-19; the CARES Act included just $3.5 billion for emergency usage of the Child Care and Development Block Grants to curb the side-effects of COVID-19 on childcare providers.[ix] Subsequently, in May 2020 the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act passed through the House, allocating a further $57 billion. The omnibus spending bill that included an additional COVID relief package that was passed in December 2020 allocated an additional $11 billion to support childcare, mostly through Child Care Development Block Grants.[x] The American Rescue Plan Act included $39 billion for the same block grants, plus a cumulative additional $39 billion in other child care support programs.[xi] Unfortunately, these funds to states have not been enough to prevent 40% of childcare centers from closing under immense economic strain.[xii]

Recommendations

- Advocate for child-serving institutions to be considered essential businesses as a baseline for economic recovery.

- Adjust state funding regulations to accommodate the necessary flexibility for child-serving institutions when an emergency is declared.

- Establish protocols to protect childcare workers as being “at increased risk” to ensure childcare programs are sufficiently staffed before reopening.

____

[i] NC Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, March 23). ChildCareStrongNC Public HealthToolkit. Retrieved from https://covid19.ncdhhs.gov/media/220/download.

[ii] Georgetown University Center for Global Health Science and Security (GHSS). (2020). COVID AMP Data Access: North Carolina. COVID AMP: Analysis and Mapping of Policies. Retrieved from https://covidamp.org/policies/USA/North%20Carolina.

[iii] Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration. Critical Facilities and Higher Standards. FEMA Media Library. Retrieved from http://data.wvgis.wvu.edu/pub/RA/_resources/CF/FPM_1_Page_CriticalFacilities_and_Higher_Standards.pdf.

[iv] US Department of Homeland Security. (2019, October 28). National Response Framework [Ebook] (4th ed.). https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/NRF_FINALApproved_2011028.pdf.

[v] Godoy, M., & Wood, D. (2020, May 30). What Do Coronavirus Racial Disparities Look Like State by State?. National Public Radio (NPR). https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/30/865413079/what-do-coronavirus-racial-disparities-look-like-state-by-state.

[vi] Jessen-Howard, S., & Workman, S. (2020, April 24). Coronavirus Pandemic Could Lead to Permanent Loss of Nearly 4.5 Million Child Care Slots. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/news/2020/04/24/483817/coronavirus-pandemic-lead-permanent-loss-nearly-4-5-million-child-care-slots/.

[vii] Malik, R. (2019, June 20). Working Families Are Spending Big Money on Child Care. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2019/06/20/471141/working-families-spending-big-money-child-care.

[viii] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation | U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2019). Factsheet: Estimates of Child Care Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2016. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/262926/CY2016-Child-Care-Subsidy-Eligibility.pdf.

[ix] Bedrick, E., & Daily, S. (2020, June 8). States Are Using the CARES Act to Improve Child Care Access during COVID-19. Child Trends. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/publications/states-are-using-the-cares-act-to-improve-child-care-access-during-covid-19#:~:text=The%20Coronavirus%20Aid%2C%20Relief%2C%20and,and%20Development%20Fund%20(CCDF)%20requirements.

[x] House Committee on Appropriations (2021, January). H.R.133 Division-by-Division Summary of COVID-19 Relief Provisions. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/133.

[xi] Senate Budget Committee (2021, March). Amendment to H.R.1319. United States Senate. Retrieved from https://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/American%20Rescue%20Plan%20Act%20SENATE.pdf.

[xii] Bell, L. (2020, May 14). Child centers say they’re still in need as they reopen to working parents. EdNC. Retrieved https://www.ednc.org/child-care-centers-reopen-working-parents-advocate-more-relief/.

Last updated: April 9, 2021