Introduction | Childcare in Disasters | Broadband in Education | Mental Health and Well-Being | Emergency Shelters and Housing Security | Food Security and Poverty | Summary

Broadband in Education: Executive Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has made broadband, or high-speed internet, an increasingly necessary service for many families as schools have transitioned to online platforms and public organizations have closed. Unfortunately, many Americans in rural areas live in internet “dead zones” where they are disconnected from access to learning and critical information during disasters. Lack of connectivity can be due to a lack of broadband infrastructure, limited network availability, prohibitive service costs, and a dearth of knowledge regarding how to get connected amidst convoluted contracting practices. Secondarily, there are also challenges with having appropriate devices to connect to networks, even when available. Modes of communication and access to broadband for education must be expanded immediately to close the “homework gap” and promote equal access to education for all children, as well as widespread access to information during disasters.

What Are Communities Saying?

Scroll to the left or right to see what communities across America are saying about internet access for children in the area.

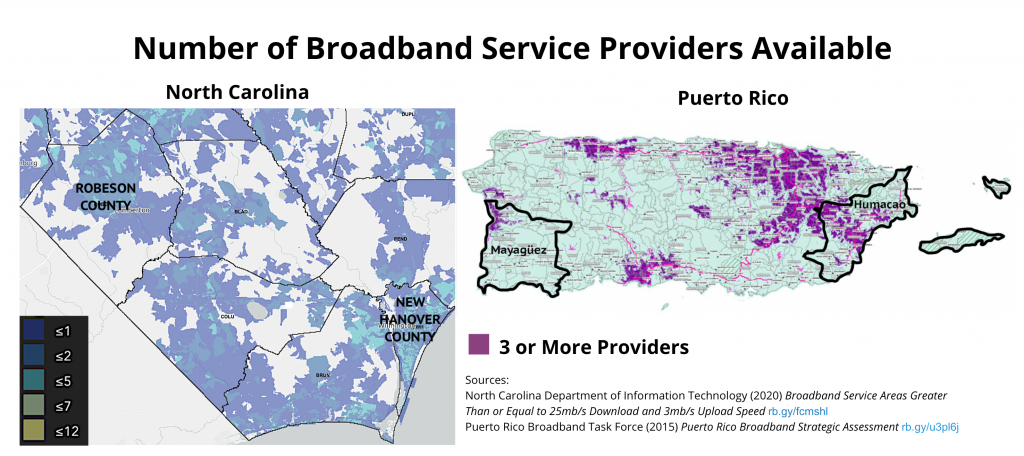

Spotlight on: Rural Areas in Robeson County, North Carolina, and the Regions of Mayagüez and Humacao in Puerto Rico

Even with resources from the CARES Act and subsequent disaster legislation, there are large internet “dead zones” across Robeson County in North Carolina and across Puerto Rico, a gap that grows even wider when considering access to high-speed broadband internet in particular. In Robeson County, over 14% of households have no broadband access due to the lack of service provision in rural areas. In Puerto Rico, 14.4% of households in the region of Mayagüez and 36.8% of households in the region of Humacao are not served by high-speed broadband internet. Unfortunately, the infrastructure is fragile and after Hurricane Maria, residents of Mayagüez and Humacao and the broader regions had no internet access at all for over 4 months. [i]

Wi-Fi in these areas is also expensive in comparison with median incomes. In Puerto Rico, the fragile internet infrastructure results in unreliable service, so 64% of households choose not to purchase internet services when comparing the value of the service against other essential household expenditures. Similarly, many families in Robeson County do not have hundreds of dollars to allot monthly for broadband access when considering the costs of necessities such as food and housing.

Community members noted that in 2019, many students were unable to complete their web-based homework or did not have access to technology in their homes, even if they were able to connect to the internet in school. Nearly 40% of Puerto Rican households do not contain a computer. Some children in Robeson County are raised by their grandparents or have parents who are essential workers, and teachers are not trained in technology to help their students engage effectively in virtual education. This makes it more difficult to identify accessibility issues and respond to the educational needs of students.

Due to the number of internet “dead zones” and the distances between community members in rural Robeson County, it can also be difficult to reach everyone through internet-based messaging and information sharing during a disaster. Many people are dependent on paper mail or community organizations, such as churches, to receive important information. During disasters, the need to supplement digital communications and ensure that these modes of communication work effectively becomes increasingly critical.

In the shaded areas with broadband service (above), multiple internet service providers (ISPs) tend to cluster around infrastructure hubs. In contrast, lack of infrastructure in rural areas leaves residents with little choice in their service options. With no or minimal competition among service providers, internet costs can be set at prices that are unaffordable for locals. In rural Robeson County, NC, 14.1% of households do not have high speed broadband access. In the Puerto Rican region of Mayagüez (western region), 14.4% of households lack broadband access, while this increases to a median of 36.8% in the region of Humacao (eastern region), largely due to the nonexistent infrastructure on the island municipalities of Culebra and Vieques.

The bar chart above shows 3 different ways that households are unable to obtain high-speed internet. Across the USA and Puerto Rico, about 1 in 5 households do not have high speed broadband service offered in their area (“No Broadband Service”). Most mainland Americans do have a computer in the house; only 11% of all mainland American households don’t have a computer, this is slightly higher (13%) for North Carolina specifically. However, almost 40% of houses in Puerto Rico don’t have a computer. As a result, and combined with the relatively high costs of service, only 36% of Puerto Rican households bother to pay for an internet subscription (compared to 85% mainland Americans) – even if the area is wired for broadband.

Meeting the Educational Needs of Children

Lack of broadband access deeply affects children, teachers, and communities. Access to broadband may also determine a family’s ability to secure education for their children in the eventual post-COVID-19 United States. The “digital divide” was a term coined two decades ago when a gap between those with internet access and those without it was acknowledged as a major factor in determining success and standard of living.[ii] The “homework gap” refers to the difficulty experienced by students who do not have consistent and reliable access to broadband at home despite the fact that it is an expectation to complete homework – a vulnerability of rural students that COVID-19 has exacerbated. In fact, in March 2020 when schools officially closed, 9 million students lacked either access to broadband services or the technology to utilize that access.[iii] COVID-19 has brought the “homework gap” and “digital divide” to the forefront of the education conversation once again as the “COVID divide.”

Lack of internet access across America is generally attributable to one or more of four obstacles:

- Availability – Broadband network access, via the provision of infrastructure or the broadcasting of service by Internet Service Providers (ISP), is not available for 20% (one fifth) of Americans.

- Costs – Service costs can be prohibitive in historically disenfranchised communities and rural areas where incomes are generally lower than in urban areas.

- Devices – Availability of internet-compatible devices sufficient for schoolwork is often a privilege in low-income areas as opposed to a quintessential resource.

- Knowledge – The knowledge of how to use devices and gain access to services and affordable programs can be opaque, especially to populations marginalized by language, literacy, or technical literacy barriers.

Pending legislation as a follow-up to the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act has attempted to address the “homework gap”. Prospective solutions include providing the funds for public libraries and schools to buy hotspots and electronic devices to connect their communities as written in the proposed HEROES Act. Low-income families would also receive $50 per month specifically to be used for internet bills.[iv] Unfortunately, sufficient resources have not been made available to date. While the CARES Act allotted $100 million for the Reconnect Pilot Program, which aims to provide grants for broadband access to rural parts of the country, it did not provide sufficient funding to cover the needs of each household lacking access.[v] Some states have used their share of the $150 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) towards increasing broadband access for education to mixed effect.[vi] The relief provisions passed in December 2020 (Public Law No: 116-260) added $7 billion in broadband initiatives, and $59 billion for education grants which are partially applicable to broadband, but service gaps in rural and tribal communities remain underfunded.[vii] Additional policies and programs are needed to help solve these infrastructural deficiencies, particularly at a time when many American families remain disconnected from equal opportunity to education and critical information.

Recommendations

- Promote and resource broadband as a public service to give all students an equal opportunity to online education during the coronavirus pandemic regardless of socioeconomic standing or geography.

- Cultivate and expand programs that further the reach of broadband access initiatives to address all four modes of inequality: (1) broadband and network access, (2) service costs, (3) technology device access, (4) technology device training in multiple languages.

____

[i] Instituto del Desarrollo de la Juventud. (2018, December). Impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico’s Children. Retrieved from https://parsefiles.back4app.com/NnOrAmAotAZqACgSOms8WkAwkOIqpZ6VWjoFVKeJ/e7cb314c136dca44c72d8570b9afb3f4_20511.pdf.

[ii] National Telecommunications and Information Administration. (1999). Falling through the net: defining the digital divide. U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved from https://www.ntia.doc.gov/legacy/ntiahome/fttn99/contents.html.

[iii] Chandra, S., Chang, A., Day, L., Fazlullah, A., Liu, J., McBride, L., Mudalige, T., & Weiss, D. (2020). Closing the K-12 Digital Divide in the Age of Distance Learning. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media. Boston, Massachusetts, Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved from https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/pdfs/common_sense_media_report_final_7_1_3pm_web.pdf.

[iv] The Heroes Act H.R. 6800 ,116th Congress (2019-2020). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6800.

[v] CARES Act S.3548, 116th Congress (2019-2020). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3548.

[vi] Pew Trusts. (2020, November 16). States Tap Federal CARES Act to Expand Broadband. Retrieved from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2020/11/states-tap-federal-cares-act-to-expand-broadband.

[vii] House Committee on Appropriations (2021, January). H.R.133 Division-by-Division Summary of COVID-19 Relief Provisions. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/133

Last updated: April 7, 2021