Introduction | Childcare in Disasters | Broadband in Education | Mental Health and Well-Being | Emergency Shelters and Housing Security | Food Security and Poverty | Summary

Food Security and Poverty: Executive Summary

In disaster-affected communities, pre-existing food insecurity and poverty present substantial challenges to building more resilient communities. Food security policies are commonly overly restrictive and emergency food programs frequently end before impoverished families have regained footing after disasters. Children relying upon school meal programs may go without meals for days at a time when disasters eliminate, alter, or otherwise stress these vital safety nets. While larger issues of generational poverty cannot be solved through food security alone, emphasizing food security throughout the entire duration of disaster recovery provides enormous relief to children and families in poverty and can help to decrease new instances of post-disaster poverty.

Food insecurity is the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways. – USDA

What Are Communities Saying?

Scroll to the left or right to see what communities across America are saying about food security and poverty

Spotlight on: Children in Poverty in Puerto Rico and North Carolina

Food insecurity and poverty are intertwined, and the compound effects are especially severe for children. To the same effect, when food security is addressed, reductions in poverty are often also observed. In North Carolina, for example, 175,000 people, including 81,000 children, were lifted out of poverty by increasing food security through Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as FNS or food stamps). The benefit also extends to the broader community, as each year over $2 billion enters the NC economy when thousands of stores participate in food stamp programs.[i]

Across the United States, trends show that where adults are food insecure, even more children are suffering. In North Carolina, 19% of adults and 26% of children are food insecure.[ii] These numbers are even higher in economically disadvantaged areas like Robeson County, where 34% of children live in homes without reliable meals and 70% of children are living in poverty.[iii] In Puerto Rico, 60% of children live in poverty[iv] and a sample of nearly 100,000 schoolchildren found that over 32% often experienced shortages in food or water.[v]

Disasters further exacerbate these issues facing families and children. In the early months of the coronavirus pandemic and following the closure of schools, North Carolinians knew that immediate measures would be necessary to keep feeding the 53% of school-age children who rely upon school lunch programs. Public schools quickly transitioned from the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) to Summer Food Service Program to gain flexibility in how and where lunches are prepared and served. In two months, cafeteria staff and bus drivers coordinated to supply over 18 million meals to food-insecure children. Distribution plans are a huge piece of the puzzle in North Carolina; without the ability to make deliveries, an estimated 75% of meals would not reach recipients.[vi] Food security in Robeson County is additionally aided by many non-governmental resources that help support the food needs of local families, such as the Lumbee Tribe, Robeson County Church and Community Center, United Way of Robeson County, Communities in Schools of Robeson County Backpack Program, food banks, and local industry partners.

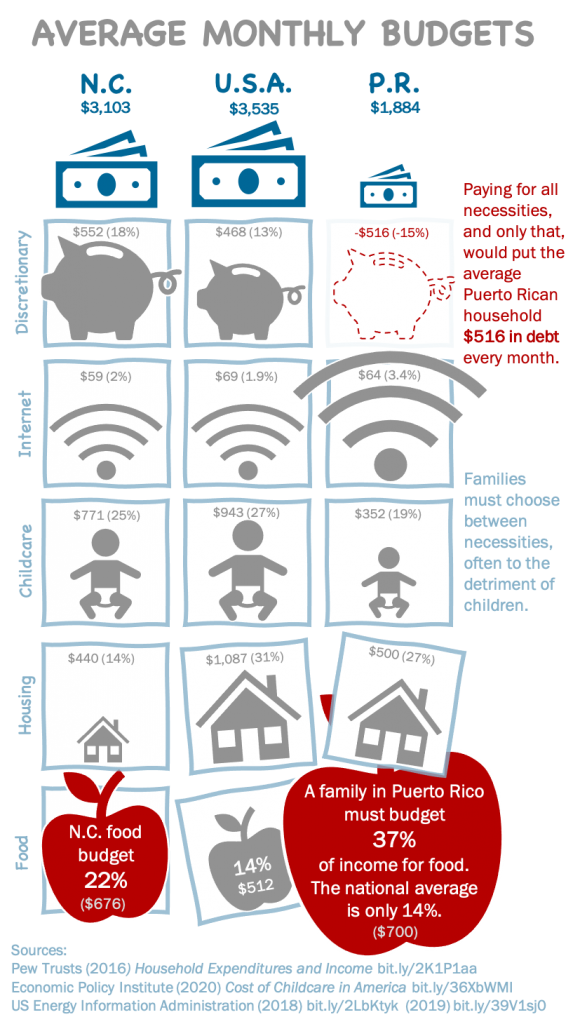

After Hurricane Maria, the Food Bank of Puerto Rico saw a 60% increase in the number of people seeking food assistance with 20% of food aid recipients enrolling in benefits for the first time.[vii] While 43% of the Puerto Rican population is food insecure, the lower middle class is 50% food insecure, and a quarter of the lower middle class couldn’t afford any meals for children at all.[viii] The aid recipients were described as often being middle class, working heads of households who did not have enough money to source food for an entire month.[ix] This description is supported by data from multiple studies that show that even just average working families in Puerto Rico and North Carolina are at increased risk for food insecurity (see infographic).

Food security after disasters in Puerto Rico is more problematic than on the mainland, due primarily to federal restrictions imposed on the island’s food stamp program, Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP, or PAN for its name in Spanish, Programa de Asistencia Nutricional). Compared to SNAP on the mainland, NAP has no automatic mechanism for providing disaster benefits. The consequence of this is that it took 6 months after Hurricane Maria for federally approved disaster nutritional assistance to reach the island. In comparison, the Virgin Islands (participating in SNAP) were able to provide food assistance within 47 days after Hurricane Maria. Although SNAP is a program for all households under the poverty line, NAP is more restrictive and only serves the bottom most income levels, yet the maximum benefits in NAP are typically about 20% lower than in SNAP.[x]

Click “play” on the interactive graphic below to see how the pandemic has affected food sufficiency for Americans. Note – A methodological change in data collection between weeks 12 and 13 resulted in increased standardized error affecting the “no answer” survey responses. For more information please refer to the Phase 2 Household Pulse Survey documentation notes here.

Meeting the Needs of America’s Hungry and Impoverished Children

The face of hunger in America is changing. Antiquated ideas of poverty and starvation conjure up images of the destitute and homeless. Instead, recent trends across America show that the working poor and vulnerable lower-middle class are at the heart of food insecurity issues. At the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, 64% of low and low-moderate income American adults were either marginally or completely food insecure. The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted existing disparities between socioeconomic and racial groups as it continues to disproportionately impact working, low-income, food-insecure families.[xi]

Yet many of the food aid programs in America, proven to alleviate poverty and provide economic benefit, are hampered by restrictions that prevent families from achieving stability in the long term. The working poor cannot afford to wait in line to pick up food or meals when they often work long hours and lack job security. Similarly, many middle-class American families without reliable access to transportation may not be able to reach aid distribution points, especially during disasters. As such, food security programs need to take into account the lifestyle restrictions induced by living in poverty and reduce barriers to obtaining benefits.

Food insecurity and poverty are especially dangerous for children because they prevent healthy brain development and create negative outcomes over the course of the child’s life, including increased exposure to violence, hunger, parents or family members in the justice system, neglect, and abuse.[xii][xiii]

The Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico has recommended an extension of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) during the COVID-19 pandemic and other disasters, specifically to aid low- and moderate-income families in stabilizing food access for children. The Disaster Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (D-SNAP) is a short-term program that serves recipients for only one month after a disaster declaration.[xvii] Since many disasters can require five or more years for a full community recovery, food security programs must be designed to support families in a bridge towards recovery for much longer than one month. The Nutritional Assistance Program (NAP) in Puerto Rico is even further chronically obstructed in delivering disaster relief due to restrictions and cuts set forth in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981, which do not apply to assistance programs on the mainland. Despite obvious limitations, NAP is the most popular food security program in Puerto Rico, with 57% of children’s families relying upon it for at least some meals. This program expired in 2019 and was re-authorized in March 2020 with $200 million during the pandemic.[xiv] Other programs authorized to provide poverty and hunger alleviation are the $8.8 billion through national Child Nutrition Programs, and $500 million for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).[xv]

The Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT) program was established in the Families First Coronavirus Act and is intended as a supplement to SNAP to assist with the childhood hunger exacerbated by the closure of schools.[xvi] This helps to alleviate some of the restrictions posed by the original National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and should be considered for long-term support as the pandemic continues to create economic hardship for families across America.

In December 2020, the additional coronavirus relief (included in Public Law No: 116-260) provided an additional total of $1.27 billion in emergency food aid and nutrition programs that benefit children. Specifically, nutrition programs such as Meals on Wheels for children were allocated an additional $180 million, another $614 million was allocated to NAP for Puerto Rico and American Samoa, and $400 million was provided to the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP). SNAP benefits were also increased by 15% per month, extended to college students, and allocated an additional $50 million for an online purchasing program.[xviii]

Recommendations

- Lengthen the duration of emergency food security programs to persist beyond short-term disaster response through the entire disaster recovery period to ensure stability for children and families.

- Prioritize food security programs in disaster-prone regions to impede increases in post-disaster poverty.

- Account for lifestyle restrictions when designing food security programs for the impoverished: reduce wait times, long lines, and other barriers to engagement for the working poor.

____

[i] North Carolina Justice Center. Hunger in N.C. Retrieved from https://www.ncjustice.org/projects/budget-and-tax-center/hunger/.

[ii] Berner, M., Vazquez, A., & McDougall, M. (2016, March). Documenting Poverty in North Carolina. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Government. Retrieved from https://www.sog.unc.edu/publications/reports/documenting-poverty-north-carolina.

[iii] UNC Chapel Hill. Hunger Research. Retrieved from https://www.sog.unc.edu/resources/tools/hunger-research.

[iv] Social Explorer, & U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). Social Explorer Tables: ACS 2017 (5-Year Estimates). Retrieved from https://www.socialexplorer.com/data/ACS2017_5yr/metadata/?ds=SE.

[v] Orengo-Aguayo, R., Stewart, R., de Arellano, M., Suárez-Kindy, J., & Young, J. (2019). Disaster Exposure and Mental Health Among Puerto Rican Youths After Hurricane Maria. JAMA Network Open, 2(4). doi: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2731679.

[vi] Childress, G. (2020). NC’s already dire childhood hunger problem has gotten a lot worse. NC Policy Watch. Retrieved from http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/2020/05/22/ncs-already-dire-childhood-hunger-problem-has-gotten-a-lot-worse/.

[vii] Save the Children, Massachusetts United Fund, & Fundacion Angel Ramos. (2018). The Impact of Hurricane Maria on Children in Puerto Rico. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/coleccionpuertorriquena/docs/instituto_juventud.

[viii] Instituto del Desarrollo de la Juventud. (2018, December). Impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico’s Children. Retrieved from https://parsefiles.back4app.com/NnOrAmAotAZqACgSOms8WkAwkOIqpZ6VWjoFVKeJ/e7cb314c136dca44c72d8570b9afb3f4_20511.pdf.

[ix] Instituto Caribeño de Derechos Humanos. (2017). Justicia Ambiental, Desigualdad y Pobreza en Puerto Rico. Retrieved from https://noticiasmicrojuris.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/final-informe-cidh-audiencia-pr-dic-2017.pdf.

[x] Keith-Jennings, B., & Wolkomir, E. (2020). How Does Household Food Assistance in Puerto Rico Compare to the Rest of the United States?. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/how-does-household-food-assistance-in-puerto-rico-compare-to-the-rest-of.

[xi] Wolfson, J. A., & Leung, C. W. (2020). Food Insecurity and COVID-19: Disparities in Early Effects for US Adults. Nutrients, 12(6), 1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061648

[xii] Tucker, W. (2019). Child Poverty in North Carolina: The Scope of the Problem [Blog]. Retrieved from https://ncchild.org/child-poverty-scope/.

[xiii] Sciamanna, J. (2020). Child Poverty in Puerto Rico. Retrieved from https://www.cwla.org/child-poverty-in-puerto-rico/.

[xiv] The Youth Development Institute of Puerto Rico. (2020). Ensuring the Success and Wellbeing of the “Maria Generation”: A Public Policy Guide. Retrieved from https://parsefiles.back4app.com/NnOrAmAotAZqACgSOms8WkAwkOIqpZ6VWjoFVKeJ/721dc9e186c743dce3068183e37038f1_45897.pdf.

[xv] Schlegelmilch, J., Rivera, A., Samur, A., Sury, J., Delgado, Y., Stewart, A., & White, Z. (2020). Children of Puerto Rico and COVID-19 Webinar Proceedings. In Children of Puerto Rico and COVID-19 – At the Crossroads of Poverty and Disaster. New York, NY: National Center for Disaster Preparedness. Retrieved from https://rcrctoolbox.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/COVID-19-PR-Webinar-Proceedings_EN_07302020.pdf.

[xvi] US Department of Agriculture. (2020). What is Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT)?. Retrieved from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/ebt.

[xvii] New York State Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance. (2019). 2019-2020 Disaster SNAP Program. Retrieved from https://otda.ny.gov/resources/NY-DSNAP-Plan.pdf.

[xviii] House Committee on Appropriations (2021, January). H.R.133 Division-by-Division Summary of COVID-19 Relief Provisions. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/133.

Last updated: April 9, 2021